Geophysics: Seeing the Invisible Beneath Our Past

Every archaeological site and heritage monument is only a partial revelation of history. What we see on the surface- ruins, standing structures, sculpted stones, walls, temples, forts, mounds, or tell-tale undulations in the landscape- is merely the visible fraction of a much larger and richer subsurface story. Beneath our feet lie buried foundations, earlier construction phases, collapsed structures, filled moats, ancient roads, drainage systems, graves, voids, tunnels, and layers of human activity accumulated over centuries or even millennia. (Image source: https://www.archaeological.org/)

Traditionally, archaeology has relied on excavation to access this hidden record. Excavation is powerful, but it is also intrusive, irreversible, time-consuming, and selective. Once the soil is removed, the original context is gone forever. In heritage settings- particularly at protected monuments, religious sites, UNESCO-listed locations, or living heritage precincts- large-scale excavation is often impractical or outright prohibited. This is where near-surface geophysics fundamentally changes the rules of engagement.

Geophysics allows us to see without digging. It provides a scientific, non-invasive window into the subsurface, enabling archaeologists and conservation professionals to visualize what lies hidden, assess its condition, and make informed decisions- before a single stone is disturbed.

At its core, geophysics is about measuring physical properties of the ground. Archaeological remains almost always differ from their surroundings in measurable ways. A stone wall has a different electrical resistivity than soil. A fired brick structure alters the local magnetic field. A buried void produces a gravity anomaly. A compacted ancient floor transmits seismic waves differently from loose fill. Near-surface geophysical methods are designed precisely to detect and map such contrasts.

What makes geophysics particularly powerful in archaeology is not just detection, but contextual understanding. Instead of isolated trenches, we can generate continuous subsurface images over large areas. Instead of speculative excavation, we can move towards hypothesis-driven investigation. Instead of reactive conservation, we can adopt preventive strategies grounded in subsurface knowledge.

In recent decades, archaeology worldwide has undergone a quiet but profound shift- from excavation-centric exploration to survey-led, data-driven investigation. Near-surface geophysics sits at the heart of this transformation. It enables archaeologists to reconstruct settlement layouts, identify activity zones, understand site evolution, and prioritize areas of significance- all while preserving the integrity of the site.

For heritage conservation, the implications are even more critical. Many historic structures fail not because of visible decay, but due to hidden subsurface problems– foundation weakness, voids, moisture ingress, buried drains, or heterogeneous ground conditions. Geophysics provides conservators and engineers with the ability to diagnose these invisible threats early, non-destructively, and systematically.

Another often overlooked dimension is ethics. Archaeology is not only about discovery; it is also about stewardship. Every excavation is a decision to destroy a part of the archaeological record in order to understand it. Geophysics offers a way to balance knowledge creation with preservation- allowing future generations, equipped with better tools and questions, to explore what we choose not to excavate today.

In essence, near-surface geophysics transforms the ground into a readable archive. It does not replace traditional archaeology; rather, it extends its vision, allowing us to think in three dimensions, across space and depth, and across time. It helps answer fundamental questions before excavation begins:

Where should we dig? Where should we not dig? What risks lie below? What stories remain hidden?

As archaeology and heritage conservation increasingly move toward sustainability, minimal intervention, and scientific rigor, geophysics is no longer optional- it is indispensable.

In the sections that follow, I will discuss how individual geophysical methods- Ground Penetrating Radar, magnetics, electrical resistivity, micro-gravity, and seismic techniques- contribute uniquely to archaeology and heritage conservation, and how their integrated use can unlock the invisible past with unprecedented clarity.

The schematic illustration combines surface observations with subsurface geophysical responses to highlight the non-invasive role of geophysics in mapping buried heritage features.

Why Geophysics Matters in Archaeology

Archaeology is fundamentally an exercise in interpretation under uncertainty. The archaeologist is asked to reconstruct human history from fragmentary evidence, much of which lies hidden below ground. Decisions about where to excavate, how much to excavate, and whether excavation is even justified have profound scientific, financial, ethical, and conservation implications. This is precisely where near-surface geophysics becomes indispensable.

From Blind Digging to Informed Exploration

Before the widespread adoption of geophysics, excavation strategies were often guided by surface indications, historical texts, chance finds, or intuition developed through experience. While these approaches have yielded remarkable discoveries, they also led to many unsuccessful trenches, unnecessary disturbance, and loss of contextual information.

Geophysics changes this paradigm by allowing archaeologists to visualize subsurface patterns before excavation. Instead of isolated trial trenches, entire buried landscapes can be mapped. Settlement layouts, street networks, building clusters, defensive structures, and activity zones can be inferred with surprising clarity. Excavation then becomes a targeted act of verification rather than an exploratory gamble.

This shift dramatically improves efficiency and scientific rigor while reducing physical impact on the site.

Preservation Through Knowledge

One of the greatest challenges in modern archaeology is balancing discovery with preservation. Excavation, by its nature, is destructive. Once an archaeological layer is excavated, it can never be re-created. In contrast, geophysics is non-invasive and repeatable. The same area can be surveyed multiple times, using different techniques, as questions evolve or new technologies emerge.

In sensitive contexts- such as burial grounds, religious sites, urban heritage precincts, or protected monuments- geophysics may be the only acceptable investigative approach. It allows researchers to respect cultural sensitivities while still advancing knowledge.

In this sense, geophysics is not merely a technical tool; it is an ethical instrument that supports responsible archaeology.

Understanding the Full Spatial Context

Excavation exposes only small windows into the subsurface. Geophysics, on the other hand, provides continuous spatial coverage. This broader view is critical for understanding how individual features relate to each other:

- How buildings are aligned within a settlement

- How open spaces, roads, and drainage systems are organized

- How different occupation phases overlap or shift spatially

- How human activity interacts with natural geomorphology

Such insights are difficult- often impossible- to obtain from excavation alone. Geophysics enables archaeology to move beyond isolated features and toward landscape-scale interpretation.

Revealing What Excavation May Miss

Not all archaeological remains are visually obvious or well preserved. Some features- such as post-holes, pits, backfilled ditches, robbed-out walls, or ephemeral structures- may leave only subtle traces in the soil. These traces can be extremely difficult to recognize during excavation, especially when stratigraphy is complex.

Geophysical methods are often more sensitive than the human eye to such contrasts. Variations in soil compaction, moisture retention, magnetic enhancement, or electrical resistivity can reveal activity that leaves little visible evidence once exposed.

In many cases, geophysics identifies archaeological features that would otherwise remain unknown.

Supporting Multi-Period and Deep-Time Archaeology

Many important archaeological sites are multi-period, with successive phases of occupation built over one another. Excavating such sites without prior subsurface understanding can lead to incomplete or misleading interpretations.

Geophysics helps disentangle this complexity by providing depth-sensitive information. Changes in physical properties with depth can hint at different construction phases, buried surfaces, or earlier settlement horizons. This allows archaeologists to design excavation strategies that respect stratigraphic integrity and prioritize key research questions.

Cost, Time, and Risk Reduction

Archaeological projects are often constrained by limited budgets and tight timelines. Large-scale excavation is expensive, labor-intensive, and logistically challenging. Failed trenches or misdirected excavation represent not only scientific loss, but financial waste.

Geophysical surveys are comparatively rapid and cost-effective, especially when covering large areas. They significantly reduce uncertainty and risk by guiding excavation toward areas of highest archaeological potential and away from sterile zones.

In development-led or rescue archaeology, this efficiency can make the difference between meaningful investigation and superficial compliance.

A Bridge Between Science and Interpretation

Perhaps most importantly, geophysics strengthens archaeology as a scientific discipline. It introduces quantitative data, spatial modeling, and hypothesis testing into what has traditionally been a largely qualitative field practice. When geophysical results are interpreted alongside excavation data, historical records, and material culture, the outcome is a far more robust and defensible narrative of the past.

Geophysics does not replace the archaeologist’s trowel or intuition. Instead, it enhances them- providing a deeper, wider, and more informed understanding of what lies beneath the surface.

Ground Penetrating Radar: The Archaeologist’s Subsurface Vision

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR)

Among all near-surface geophysical techniques used in archaeology, Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) occupies a special place. It comes closest to fulfilling what archaeologists have always wished for: the ability to see buried structures in plan view, understand their depth, and visualize their geometry before excavation. In many respects, GPR has reshaped archaeological prospection more than any other single method.

Why GPR is So Powerful in Archaeology

GPR works by transmitting short pulses of electromagnetic energy into the ground and recording reflections generated at interfaces where material properties change. Archaeological features almost always create such interfaces: stone against soil, brick against fill, compacted floors beneath loose sediments, voids beneath intact layers.

What makes GPR particularly valuable is its ability to provide high-resolution, depth-controlled information. Unlike many surface methods, GPR does not simply indicate the presence of an anomaly; it helps answer three critical archaeological questions simultaneously:

- Where is the feature located laterally?

- At what depth does it occur?

- What is its likely geometry and continuity?

This three-dimensional perspective is transformative for both research-driven and conservation-oriented archaeology.

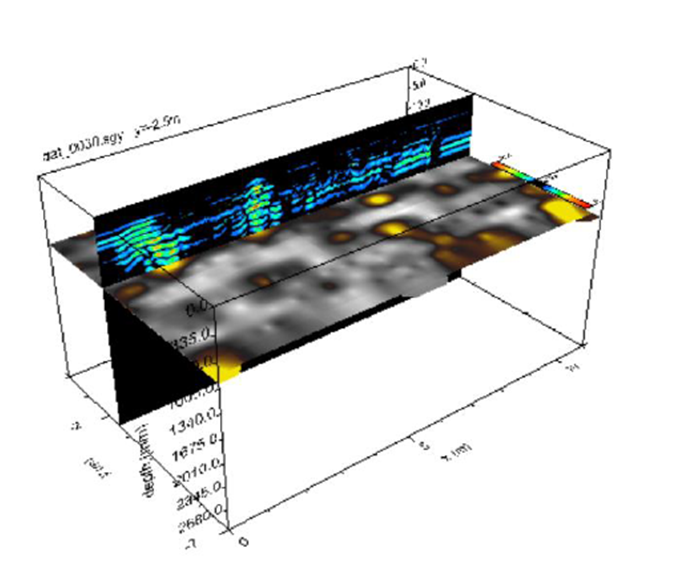

High quality, depth controlled information – GPR

Mapping Buried Architecture Without Excavation

One of the most successful applications of GPR is the detection and mapping of buried architectural remains. Walls, foundations, pavements, courtyards, staircases, and floor levels often produce strong, coherent reflections. When surveyed in dense grids, GPR data can be processed into horizontal depth slices that resemble excavation plans.

In many cases, these depth slices reveal complete building layouts: room arrangements, wall alignments, entrances, and circulation patterns. Archaeologists can reconstruct settlement organization and architectural logic without disturbing the ground. Excavation, if undertaken later, becomes precise and purposeful rather than exploratory.

This capability is especially valuable at sites where excavation is restricted due to religious, legal, or conservation constraints.

Understanding Construction Phases and Site Evolution

Archaeological sites are rarely single-period. Most represent layers of occupation, rebuilding, abandonment, and reuse. GPR excels in such contexts because reflections occur at multiple depths. Shallow reflections may represent recent phases, while deeper reflections may correspond to earlier construction or occupation horizons.

By analyzing reflection patterns and their depth distribution, archaeologists can begin to infer construction sequences and site evolution. This helps frame excavation questions more intelligently and avoids misinterpretation of complex stratigraphy.

Detection of Voids, Chambers, and Tombs

Another major strength of GPR is its sensitivity to voids and air-filled spaces. Tombs, crypts, burial chambers, underground passages, and cavities produce distinctive reflection signatures due to the strong contrast between air and surrounding materials.

In heritage contexts, this application is particularly critical. Many historic monuments rest above unknown voids that pose structural risks. GPR allows these features to be detected and mapped non-invasively, supporting both archaeological interpretation and structural safety assessment.

Applications in Standing Monuments and Heritage Structures

GPR is not limited to open archaeological sites. It is widely used within standing heritage structures, including temples, churches, mosques, forts, and palaces. Applications include:

- Mapping foundations beneath floors without lifting slabs

- Detecting earlier construction phases hidden within walls

- Locating buried drains, channels, and services

- Assessing moisture ingress and internal deterioration zones

For conservation professionals, GPR provides diagnostic information that would otherwise require destructive testing.

Limitations and the Importance of Expertise

Despite its strengths, GPR is not a universal solution. Its effectiveness depends strongly on ground conditions. Highly conductive soils, clay-rich sediments, or saline moisture can severely limit penetration depth. Data interpretation is also complex and requires experience, archaeological context, and integration with other methods.

Used indiscriminately, GPR can produce misleading results. Used intelligently, it becomes an exceptionally powerful tool.

GPR as Part of an Integrated Approach

The most successful archaeological investigations do not rely on GPR alone. Instead, GPR is combined with magnetics, resistivity, gravity, or seismic methods depending on site conditions and research objectives. Such integration reduces ambiguity and strengthens interpretation.

In modern archaeology, GPR has moved from being a specialist technique to a core component of survey-led investigation. It bridges the gap between surface observation and excavation, offering a detailed, non-invasive preview of the past.

Magnetic Methods: Tracing Human Activity Across Ancient Landscapes

Magnetic surveying is one of the most widely used and cost-effective geophysical techniques in archaeology. While it may not always produce visually striking images like Ground Penetrating Radar, its ability to rapidly cover large areas and sensitively detect traces of past human activity makes it indispensable, particularly in landscape-scale archaeology.

Conceptual illustration of a magnetic survey at an archaeological site. The Geophysicist is shown traversing a predefined grid with a Magnetometer and subsurface anomalies represent buried archaeological artefacts with measurable magnetic contrasts.

Why Human Activity Leaves Magnetic Signatures

Most archaeological features alter the natural magnetic properties of the soil in subtle but measurable ways. Human actions such as digging, backfilling, burning, construction, and waste disposal disturb the original soil structure and often enhance its magnetic susceptibility.

Fired materials such as bricks, tiles, pottery, and hearths acquire thermoremanent magnetization during heating and cooling. Organic occupation layers enrich soils with iron oxides over time. Even features that have been robbed out or completely collapsed, such as walls or ditches, often remain magnetically visible long after they have disappeared from view.

Magnetic methods exploit these contrasts to map archaeological features that may have no surface expression at all.

Rapid Mapping of Settlements and Cultural Landscapes

One of the greatest strengths of magnetics is speed. Large areas can be surveyed quickly with minimal ground contact. This makes magnetic surveys ideal for:

- Mapping settlement extents and internal organization

- Identifying houses, enclosures, streets, and activity zones

- Tracing ancient field systems, canals, and roads

- Reconnaissance of unexplored archaeological landscapes

Entire buried towns have been outlined using magnetics alone, providing a spatial framework that guides targeted excavation and further detailed investigation.

Exceptional Sensitivity to Fired and Burnt Features

Magnetic methods are particularly effective in detecting features associated with fire. Kilns, furnaces, hearths, brick-lined drains, and burnt floors often produce strong magnetic anomalies that stand out clearly against the background.

In many prehistoric and early historic sites, such features represent key evidence of industrial activity, domestic life, and technological development. Magnetic surveys can therefore play a crucial role in identifying specialized activity areas within settlements.

Revealing the Invisible and the Ephemeral

Not all archaeological remains are monumental. Some of the most important evidence of human behaviour lies in ephemeral features such as post-holes, pits, refuse zones, and shallow ditches. These features may be extremely difficult to recognize during excavation, especially when soil colour contrasts are subtle.

Magnetics often detects these features more effectively than excavation itself, revealing patterns of occupation and land use that would otherwise remain invisible.

Limitations and Environmental Considerations

Despite its strengths, magnetic surveying is sensitive to modern interference. Buried utilities, fences, vehicles, reinforced concrete, and surface debris can obscure or distort archaeological signals. Geological background also matters. In some regions, highly magnetic bedrock or soils can reduce contrast and complicate interpretation.

As with all geophysical methods, success depends on careful survey design, experienced data processing, and archaeological insight.

Role in Heritage Conservation and Management

Magnetics is increasingly used not only for discovery but also for heritage management. By defining the extent of buried archaeology, it helps planners and conservators avoid unnecessary disturbance during development, landscaping, or restoration work.

In protected sites, magnetic maps often form the basis of long-term management plans, identifying zones of high archaeological sensitivity that should remain untouched.

Magnetics as the First Step in Integrated Surveys

In many archaeological projects, magnetic surveying serves as the first investigative step. It provides a rapid, low-cost overview that helps determine where more detailed methods such as GPR or electrical resistivity should be applied.

Used in this strategic manner, magnetic methods act as the foundation of a tiered, integrated geophysical approach.

Electrical Resistivity Methods: Mapping Stone, Voids, and Moisture in the Subsurface

Electrical resistivity methods have a long and respected history in archaeological investigation. Long before advanced digital instruments and 3D imaging became available, archaeologists relied on resistivity surveys to locate buried walls and foundations. Today, with the advent of Electrical Resistivity Imaging (ERI), the method has evolved into a powerful tool capable of providing both lateral and depth-resolved information critical to archaeology and heritage conservation.

The Physical Basis and Archaeological Relevance

Electrical resistivity surveys work by injecting a small electrical current into the ground and measuring how strongly the subsurface resists the flow of that current. Different materials conduct electricity differently. Stone, masonry, and voids tend to be more resistive, while moist soils, clays, and organic fills are typically more conductive.

Archaeological features almost always disturb the natural resistivity distribution of the ground. Buried stone walls, foundations, floors, tombs, and drainage structures create resistivity contrasts that can be mapped with remarkable clarity.

Detection of Buried Architecture and Foundations

One of the most reliable applications of resistivity methods is the identification of stone-built features. Foundations, walls, and paved surfaces often appear as high-resistivity anomalies relative to surrounding soils.

In heritage sites where standing monuments exist, resistivity imaging can extend our understanding below ground. It helps answer practical questions such as how deep foundations extend, whether earlier construction phases exist beneath visible structures, and whether subsurface heterogeneity could affect structural stability.

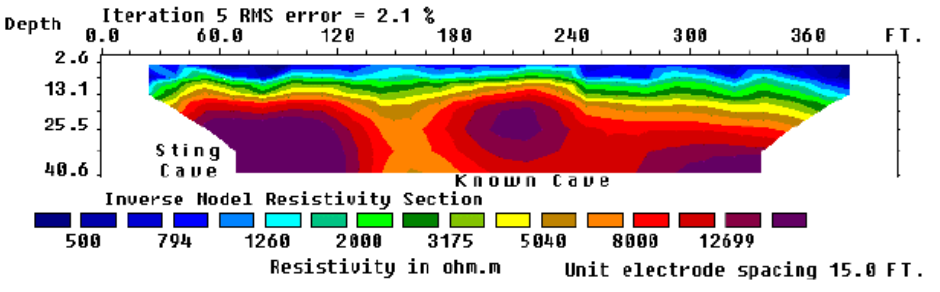

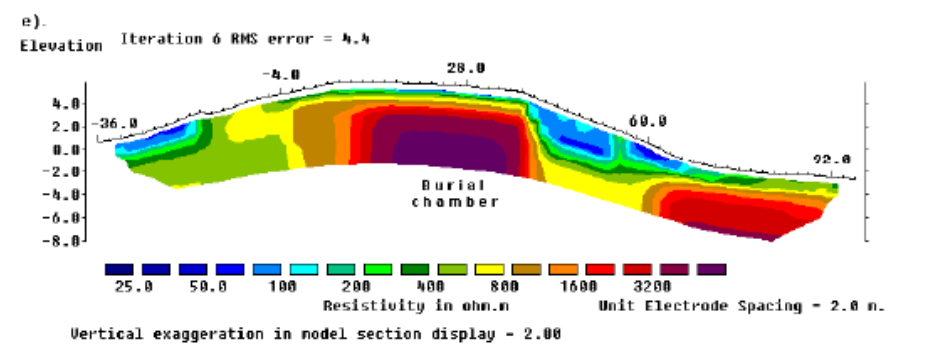

Locating Voids, Chambers, and Subsurface Cavities

Voids, crypts, tunnels, and burial chambers are typically highly resistive compared to surrounding materials. Resistivity imaging is therefore particularly effective in detecting such features, especially when penetration depth beyond the reach of GPR is required.

In conservation contexts, this application is critical. Undetected cavities beneath monuments can lead to differential settlement or collapse. Resistivity surveys provide a non-invasive means of identifying and mapping these hidden risks.

Understanding Moisture and Drainage Conditions

Moisture is one of the most destructive agents affecting archaeological remains and heritage structures. Rising damp, seepage, leaking drains, and water accumulation accelerate decay and weaken foundations.

Electrical resistivity is highly sensitive to moisture content. Low-resistivity zones often indicate water pathways, saturated layers, or leaking drainage systems. By mapping these zones, conservators can diagnose moisture-related problems and design targeted remedial measures.

2D and 3D Imaging for Complex Sites

Modern ERI allows archaeologists to move beyond simple anomaly detection toward detailed subsurface models. Two-dimensional profiles can reveal vertical stratigraphy, while three-dimensional resistivity models provide volumetric views of buried features.

Such imaging is invaluable at complex, multi-period sites where features overlap spatially and vertically. It also supports integration with GPR and magnetic data, reducing ambiguity and improving interpretative confidence.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Resistivity surveys require good electrode contact with the ground, which can be challenging on paved surfaces, rocky terrain, or within standing monuments. Survey speed is generally slower than magnetic methods, and careful design is needed to balance resolution and depth.

Despite these limitations, resistivity remains one of the most robust and interpretable geophysical methods in archaeology, particularly when stone construction and moisture processes are involved.

Illustrative visualization of an Electrical Resistivity Imaging (ERI) survey applied to Archaeology.

A Key Tool for Heritage Conservation

In heritage conservation, electrical resistivity methods bridge the gap between archaeology and engineering. They provide subsurface information that informs both historical interpretation and structural assessment.

Used strategically, resistivity imaging supports preventive conservation by identifying hidden problems before they manifest as visible damage.

Micro-Gravity and Seismic Methods: Detecting Voids, Stability, and Hidden Risks

While methods such as GPR, magnetics, and resistivity are widely used in archaeology, micro-gravity and seismic techniques address a different but equally critical question: Is the ground beneath a heritage site structurally sound? These methods are particularly valuable where safety, stability, and long-term conservation are primary concerns.

Micro-Gravity: Seeing the Absence of Mass

Micro-gravity surveying measures extremely small variations in the Earth’s gravitational field caused by changes in subsurface density. Archaeologically and conservationally, this makes micro-gravity uniquely sensitive to voids and cavities.

Subsurface features such as tombs, crypts, tunnels, collapsed chambers, and karstic cavities represent zones of reduced density. Even when completely filled or inaccessible, these features can still produce measurable gravity lows.

Micro-gravity is especially valuable in situations where other methods struggle:

- Beneath thick masonry or stone flooring

- In urban heritage settings with limited surface access

- Where GPR penetration is poor due to conductive soils

- When void detection is the primary objective

For historic monuments, this capability is critical. Many structural failures originate from undetected cavities beneath foundations. Micro-gravity provides a non-invasive means of identifying such hazards before visible distress occurs.

Conceptual depiction of a microgravity survey at a heritage site. The gravimeter setup and gravity anomaly exhibit how low density features like cavities, chambers or passages can be identified beneath archaeological remains.

Seismic Refraction: Understanding Foundation and Bedrock Conditions

Seismic refraction methods are based on measuring the travel times of seismic waves as they pass through subsurface layers with different elastic properties. In archaeology and heritage conservation, this method is primarily used to:

- Determine depth to bedrock beneath monuments

- Identify weathered or fractured zones

- Assess foundation support conditions

- Map major subsurface discontinuities

Many historic structures were built directly on rock or shallow foundations. Changes in bedrock depth or quality can strongly influence long-term stability. Seismic refraction provides this information without excavation.

MASW: Mapping Ground Stiffness Beneath Heritage Structures

Multichannel Analysis of Surface Waves (MASW) has emerged as a powerful tool for evaluating near-surface stiffness variations. By analyzing surface wave dispersion, MASW provides shear wave velocity profiles that reflect the mechanical competence of subsurface materials.

In heritage contexts, MASW is particularly useful for:

- Identifying weak zones beneath monuments

- Evaluating differential stiffness that may cause uneven settlement

- Supporting seismic vulnerability assessments

- Complementing structural analysis of historic buildings

Because MASW surveys can often be conducted along accessible pathways or open courtyards, they are well suited to sensitive heritage environments.

Seismic Tomography: Imaging Complexity in Three Dimensions

Cross-hole and surface seismic tomography offer high-resolution imaging of subsurface velocity variations. These methods are invaluable where complex conditions exist, such as:

- Layered construction phases

- Mixed natural and anthropogenic materials

- Zones of deterioration beneath large monuments

Tomographic images help conservators understand how subsurface conditions vary spatially, allowing for targeted intervention rather than blanket remedial measures.

Role in Risk Assessment and Preventive Conservation

Micro-gravity and seismic methods shift archaeology and heritage conservation from discovery alone toward risk-informed management. They help answer questions such as:

- Are there hidden voids that threaten stability?

- Is the foundation material uniform and competent?

- Where are the weakest zones beneath the structure?

By identifying problems early, these methods support preventive conservation, reducing the likelihood of sudden failures and costly emergency interventions.

Seismic Survey Methods to Aid Archaeology, non-invasively.

Integration with Other Geophysical Methods

On their own, micro-gravity and seismic techniques can be ambiguous. Their true strength emerges when integrated with GPR, resistivity, and magnetics. A gravity low corroborated by a resistivity high and a seismic low-velocity zone provides compelling evidence of a cavity or weakened ground.

Such multi-method integration is increasingly becoming best practice in heritage investigations.

The Integrated Geophysical Approach: From Isolated Anomalies to Reliable Interpretation

No single geophysical method can answer all archaeological or conservation questions. Each technique responds to a specific physical property of the ground and each has its own strengths, limitations, and sensitivities. The true power of near-surface geophysics in archaeology and heritage conservation emerges when multiple methods are integrated into a coherent investigative strategy.

Why Integration is Essential

Archaeological features are complex. A buried wall may be stone-built, moisture-affected, partially collapsed, and cut by later disturbances. One method may highlight it clearly, another may respond weakly, and a third may reveal associated features that are not visible otherwise.

For example:

- GPR may map wall geometry and depth

- Electrical resistivity may confirm stone construction and moisture conditions

- Magnetics may reveal associated activity areas or earlier phases

- Seismic methods may assess foundation competence beneath the structure

Individually, each dataset provides partial insight. Together, they form a consistent and defensible interpretation.

Reducing Ambiguity and False Positives

One of the biggest risks in archaeological geophysics is over-interpretation. Many non-archaeological features such as tree roots, geological variations, or modern disturbances can produce anomalies that mimic cultural remains.

Integration reduces this risk. When an anomaly appears in multiple independent datasets, the confidence in its archaeological origin increases dramatically. Conversely, anomalies that appear in only one dataset can be flagged for cautious interpretation or further verification.

This cross-validation is especially important in high-stakes heritage contexts where intrusive investigation is limited or impossible.

Designing Surveys Around Archaeological Questions

An integrated approach begins not with instruments, but with questions. What is the objective of the investigation?

- Locating buried architecture

- Mapping settlement layout

- Detecting voids and chambers

- Assessing foundation stability

- Understanding moisture and deterioration processes

Survey design then follows logically. Broad reconnaissance may start with magnetics. Detailed mapping may rely on GPR and resistivity. Stability assessment may require seismic and micro-gravity methods. This tiered strategy ensures efficiency and relevance.

3D Subsurface Models and Digital Heritage

Modern geophysics allows the creation of three-dimensional subsurface models that integrate data from multiple methods. These models can be visualized alongside excavation plans, architectural drawings, and historical maps.

For heritage managers, such models become powerful decision-support tools. They help plan conservation interventions, manage visitor infrastructure, and assess long-term risks without repeated excavation or testing.

Integrated geophysical models are increasingly forming the basis of digital heritage documentation and site management plans.

Collaboration Between Disciplines

Effective integration requires close collaboration between geophysicists, archaeologists, architects, engineers, and conservators. Geophysical data must be interpreted within archaeological context, while archaeological hypotheses must respect geophysical constraints.

When this dialogue is strong, geophysics moves beyond service provision and becomes a genuine research partner in archaeological discovery and heritage protection.

Toward Best Practice in Archaeological Geophysics

Across the world, best practice guidelines increasingly emphasize integrated surveys rather than single-method deployments. This reflects a growing recognition that heritage sites are complex systems, not isolated features.

Integrated geophysics supports:

- Better science

- Reduced risk

- Minimal intervention

- Sustainable conservation

It aligns perfectly with the modern ethos of archaeology and heritage management.

Geophysics in Heritage Conservation: From Diagnosis to Preventive Management

While archaeology often focuses on discovery and interpretation, heritage conservation is primarily concerned with protection, stability, and longevity. Many threats to heritage structures originate below ground and remain invisible until damage becomes severe or irreversible. Near-surface geophysics plays a crucial role in shifting conservation practice from reactive repair to preventive, knowledge-driven management.

Understanding What Lies Beneath Standing Monuments

Historic monuments are rarely founded on uniform ground. Over centuries, changes in drainage, groundwater levels, seismic activity, and human intervention alter subsurface conditions. Foundations may rest partly on rock and partly on fill. Hidden voids may develop due to decay, leakage, or dissolution.

Geophysical investigations allow conservators to understand:

- Foundation depth and extent

- Variations in subsurface stiffness and competence

- Presence of voids, cavities, or weakened zones

- Interaction between built structures and natural geology

This information is essential for diagnosing the root causes of visible distress such as cracking, tilting, or settlement.

Geophysics in Heritage Conservation.

Moisture as a Silent Destroyer

Moisture is one of the most damaging agents affecting heritage structures. Rising damp, seepage from buried drains, water accumulation, and seasonal saturation accelerate material decay, salt crystallization, and biological growth.

Electrical resistivity and GPR are particularly effective in mapping moisture distribution beneath and around monuments. Low-resistivity zones and GPR attenuation patterns often highlight water pathways that are not visible at the surface.

By identifying these pathways, conservation interventions can be targeted and effective, addressing causes rather than symptoms.

Assessing Structural Safety Without Intrusion

Traditional structural investigations often require drilling, coring, or test pits, all of which introduce new risks to fragile structures. Geophysics provides a non-invasive alternative.

Micro-gravity surveys detect hidden cavities beneath floors and foundations. Seismic methods evaluate ground stiffness and load-bearing capacity. Together, these techniques help assess structural safety without compromising the integrity of the monument.

This approach is especially valuable for iconic or protected structures where intrusive testing is unacceptable.

Supporting Conservation Design and Engineering Decisions

Conservation projects increasingly involve engineering solutions such as underpinning, drainage improvement, grouting, or ground strengthening. Poor understanding of subsurface conditions can lead to ineffective or even harmful interventions.

Geophysical data supports informed design by:

- Defining the extent of treatment zones

- Identifying areas that require intervention and areas that should remain untouched

- Reducing uncertainty in conservation engineering

In this way, geophysics acts as a bridge between heritage conservation and geotechnical engineering.

Long-Term Monitoring and Change Detection

Heritage conservation is not a one-time activity. Conditions evolve over time due to environmental change, urban development, climate variability, and visitor load.

Repeat geophysical surveys allow monitoring of:

- Changes in moisture distribution

- Development or expansion of voids

- Progressive weakening of subsurface materials

Such monitoring supports early warning and timely intervention, extending the life of heritage structures with minimal disturbance.

Geophysics as a Tool for Sustainable Conservation

Sustainable heritage conservation aims to minimize intervention while maximizing understanding. Near-surface geophysics aligns perfectly with this philosophy. It provides critical subsurface knowledge while preserving the physical and cultural integrity of heritage sites.

By integrating geophysics into routine conservation practice, heritage managers can move from crisis-driven repairs to planned, preventive care.

The Way Forward: Geophysics as the Backbone of Sustainable Archaeology and Heritage Conservation

Archaeology and heritage conservation are entering a phase where non-invasive knowledge, digital documentation, and long-term stewardship are becoming more important than large-scale excavation. In this evolving landscape, near-surface geophysics is no longer a supporting technique. It is steadily becoming the backbone of responsible investigation and conservation practice.

From Discovery to Stewardship

The role of geophysics is expanding beyond discovery. Increasingly, it is being used to support decisions about what should be excavated, what should be preserved in situ, and how sites should be managed over decades rather than years.

This shift reflects a broader philosophical change in archaeology. The objective is no longer only to uncover the past, but to protect it intelligently, using scientific evidence to guide minimal and reversible intervention.

Integration with Digital Archaeology and Heritage Management

Geophysical datasets are inherently spatial and three-dimensional. When integrated with GIS platforms, photogrammetry, laser scanning, and historical documentation, they contribute to comprehensive digital models of heritage sites.

These models allow:

- Visualization of buried archaeology alongside standing structures

- Scenario testing for conservation and visitor management

- Better communication between scientists, conservators, authorities, and the public

Geophysics thus plays a central role in creating digital twins of heritage sites that support informed and transparent decision-making.

Role of Advanced Processing, AI, and Automation

Advances in data processing, machine learning, and pattern recognition are beginning to transform archaeological geophysics. Automated anomaly detection, assisted interpretation, and probabilistic mapping are reducing subjectivity and improving consistency.

While expert judgment remains irreplaceable, these tools help manage large datasets and reveal subtle patterns that may otherwise be overlooked. In the future, geophysics will increasingly support predictive archaeology, guiding investigations before development or conservation pressures arise.

Climate Change and Increasing Risk to Heritage

Climate change is emerging as a major threat to archaeological and heritage sites. Rising groundwater levels, increased flooding, temperature extremes, and changing soil moisture regimes directly affect subsurface conditions.

Geophysical monitoring provides a means to understand and track these changes. By observing variations in moisture, stiffness, and void development over time, conservators can anticipate damage rather than react to it.

In this context, geophysics becomes a tool not just for the past, but for safeguarding heritage in an uncertain future.

Building Capacity and Interdisciplinary Collaboration

For geophysics to realize its full potential, it must be integrated early into archaeological planning and heritage policy. This requires training archaeologists to understand geophysical outputs and geophysicists to appreciate archaeological context.

The most successful projects are those where collaboration is continuous rather than transactional. When geophysics is embedded within interdisciplinary teams, interpretation becomes richer and outcomes more sustainable.

A Closing Reflection

Every generation inherits the past in trust. We are custodians, not owners, of archaeological and heritage resources. Near-surface geophysics offers a rare balance between curiosity and responsibility. It allows us to explore without destroying, to diagnose without damaging, and to plan without guessing.

As pressures on land, infrastructure, and heritage continue to grow, the role of geophysics will only become more central. It is not simply a set of tools, but a way of thinking about the ground as an archive that deserves to be read carefully, respectfully, and scientifically.

The future of archaeology and heritage conservation will be written not only by what we excavate, but by what we choose to understand and preserve unseen.